True? Or False? "Sugar and carbohydrates are the enemy of anyone wanting a healthy diet.” False.

By Craig Hunt, RD & Nutritionist

When seeing a movie, reading a magazine, or over-hearing a conversation, chances are there will be a reference to sugar. Sugar has reached a new low in its possible connection to obesity, and therefore eating it is akin to wearing the nutritional dunce cap. Along with sugars sentencing to the nutritional gallows, other foods have been implicated in the war on obesity, such as potatoes, and wheat products such as bread and pasta, and let’s not forget white rice. So what do all of these foods have in common, and how can they be linked with sugar? It’s a multi-fold answer that involves chemical structure, digestive enzymes, and a blood sugar response rating system called the glycemic index.

Let’s begin with taking a look under the hood at the structure of these foods. All of the foods contain what are called complex carbohydrates, which are long chains of sugar molecules linked together. Almost all foods contain some type of carbohydrate – including meat, which is called glycogen. However, the amount in meat is very small compared to the amounts in grains, potatoes, and legumes. Your body has digestive enzymes that it uses to break apart the long chains of sugar molecules; the first enzyme is secreted in your mouth from your salivary glands. The second area for dismantling the sugar chains occurs in your upper-small intestine, in an area called the duodenum. The duodenum receives pancreatic digestive enzymes which break the glucose chains into smaller sugar chains. Finally, an area of your small intestine called the brush border, intestinal enzymes reduce the sugars into the individual units of glucose, fructose, and galactose. Fruits, vegetables, and high-fructose corn sweetener are primary sources of fructose. Galactose is a simple sugar found in milk and dairy products.

Once the sugars are absorbed they travel through your blood to the liver, where fructose and galactose are further modified to become glucose – sugar. Even though glucose (sugar) has become a nutritional bad-boy, it have several extremely important functions in the body, such as becoming a storage form of carbohydrate in our liver, helping our body regulate blood sugar levels throughout the day, or when you choose to not eat breakfast. Glucose also is stored in muscle tissue, called muscle glycogen, so our muscles have easy access to fuel for movement. Glucose is also part of our DNA, and its primary function is to provide cells with a source of energy. Surprisingly, your body can also convert it into a building block called an amino acid, and glucose cn also can be converted into fat for storage.

Fiber is another form of complex carbohydrate important for our health. Fiber is made up of long chains of sugar (glucose) molecules, but humans lack the digestive enzymes to break the sugar molecules apart, so the large chains of glucose molecules travel all the way to your large colon where they are digested (fermented) by friendly digestive bacteria.

So now we’ve seen two the sides of glucose, one that can be broken down by our digestive enzymes, and another (fiber) that cannot. The glycemic index has become a common “rating system” for evaluating how quickly a food will turn into usable blood glucose. If you’re running in race, or having a low blood sugar reaction, then consuming foods with a high (fast to glucose) glycemic index is preferred. Many people in triathalons, and marathons use fast-acting glucose products such as a sports gel to keep their blood sugars from crashing during an event.

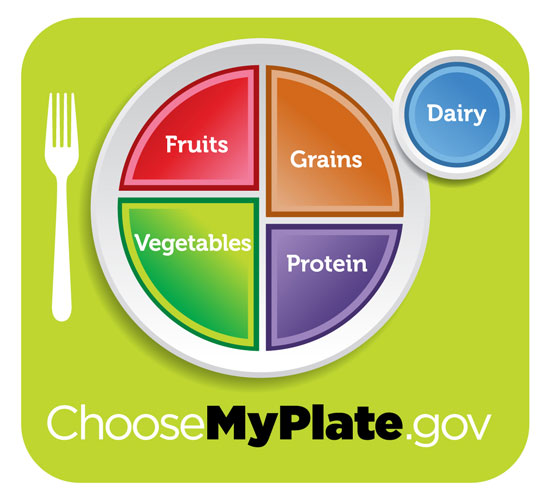

To further explain the glycemic index, glucose has a glycemic index of 100, a baked potato has a glycemic index (GI) of 85, and a bagel has a GI of 72. Anything over 70 is considered a high glycemic index. White rice has a GI of 56, which is considered medium value. Apples have a GI of 38, which is a low value. So what does all of this really mean to Jane and Joe Public? A common interpretation is, “if it’s fast to blood sugar, then we should avoid it”. If only it were that simple! When you eat a potato, do you just sit down to a large baker - and that’s your entire meal? According to Myplate.gov, and most dietitians, that’s not a balanced way to eat.

Using the MyPlate image as a reference, if you place the bread, or rice or pasta, on the plate in the upper right-side (see grains), you can see that more food sources are recommended at the meal, vegetables, fruits, protein, and a dairy/calcium source. Each of the food groups having very differing glycemic indexes, yet when consumed together, there is a complicated digestive process that takes place in over 20-feet of digestive tract, beginning in your mouth. Meals that contain protein, fat, and fiber are more slowly digested, which also affects how quickly the accompanying carbohydrates are digested.

Using the MyPlate image as a reference, if you place the bread, or rice or pasta, on the plate in the upper right-side (see grains), you can see that more food sources are recommended at the meal, vegetables, fruits, protein, and a dairy/calcium source. Each of the food groups having very differing glycemic indexes, yet when consumed together, there is a complicated digestive process that takes place in over 20-feet of digestive tract, beginning in your mouth. Meals that contain protein, fat, and fiber are more slowly digested, which also affects how quickly the accompanying carbohydrates are digested.

So even though a potato, or bagel on its own would be quickly digested and absorbed, that’s usually not the case in how these foods are eaten. Potatoes also possess other valuable nutrients, such as being extremely high in potassium – a third more than bananas, and a significant source of fiber, and iron. With this type of nutritional line up, why has the potato been placed equal footing as sugar? More clues reside in the fact that Americans love their French fries. It’s the most preferred source of potato in the American diet. So, rather than banish the potato for its high glycemic index, and penchant for been fried, this affordable, nutrient dense food can simply be served in its whole, skin-on state, either baked or steamed, or mashed. It doesn’t require any extra fat wrapping, and just like a bagel doesn’t have to be smothered in cream cheese.

In 1994 the National Academy of Sciences established the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) to establish nutrient requirements for all Americans. The amount set for carbohydrates is 130 grams per day, which is considerably lower than the Daily Value levels on Nutrition Facts labels. The National Academy of Sciences published our nation’s first set of dietary standards in 1943, called the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs). These guidelines were designed to help a country struggling with malnutrition from under nourishment, as evidenced by the many men who could not pass their military physicals for World War II.

Now, our country is learning how to cope with another form of malnutrition, called over nutrition. We are consuming an abundance of extra empty calories from a variety of sources such as soda, refined grain products, and alcohol. There are many theories about why this has occurred, and many people, including health professionals, see sugar as the bull’s eye, as well as any foods, that quickly convert to sugar. Instead of finger pointing and eschewing certain foods, the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans has many science-based recommendations. For instance, the simple recommendation of “increasing vegetables and fruits”, for a variety of reasons, goes unheeded by many Americans. Or, the recommendation to “choose a variety of protein foods, including seafood, lean meat, poultry, eggs, beans, peas, soy products, and unsalted nuts and seeds” – has not curbed people’s double cheese burger habits. And finally, “account for all foods and beverages consumed and assess how they fit within a total healthy eating pattern”, puts the onus on people to be mindful about their food choices.

There are many nutritional scapegoats, and easy targets are found on every shelf of the super market. Our government is encouraging us to take appropriate action, and if we each take some small or large steps toward making healthier choices, they’ll be no need demonize sugar, potatoes, wheat, soda, or anything else with calories. By focusing more on what we can “add” into our eating habits, we’ll be less preoccupied with what needs to be removed – which ultimately leaves a person wanting that food even more.